Story

Story

The Space-Age Mall with a New Future

Reviving a Shopping Center to Preserve a Communityʼs Gathering Place

Yuji Hokazono looks out over the craft fair taking place in the atrium of the Miyako City shopping mall and recalls a time, almost a half-century ago, when the mall offered a vision of a more glittering, space-age future.

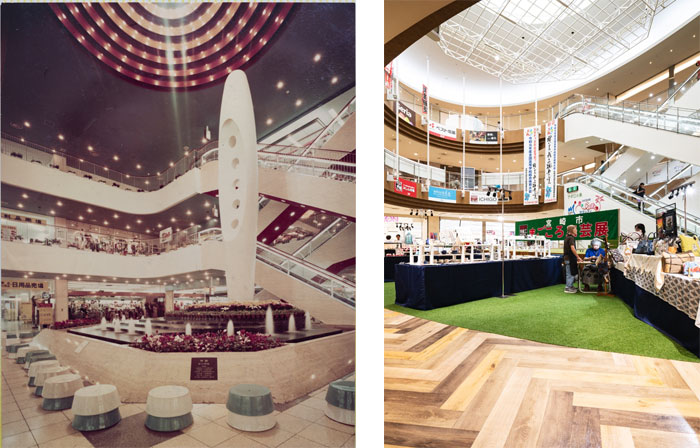

That was 1973, when Miyako City opened to much fanfare as the first indoor shopping mall in Miyazaki, a rural prefecture on Japanʼs southern island of Kyushu. Wide-eyed crowds gawked at the mallʼs array of shopping and entertainment offerings, which included a swimming pool, skating rink, amusement park, and aerospace museum with its own biplane and two planetariums.

The atrium was dominated by the Apollo Fountain, a soaring, two-story white obelisk commemorating the first Moon landing just four years before.

Hokazono, 62, says Miyako City was his first encounter with the new consumer culture that was spreading from urban centers like Tokyo.

‟I was actually scared to come at first,” says Hokazono, who was a teenager at the time, and traveled an hour and a half by bus to get there. ‟Iʼd never seen anything so large, and so full of people.”

Today, the Apollo Fountain is long gone, but the crowds are back, seeking something different.

On a recent afternoon, the mall is filled with people who appear very much at home. Some gather to chat over cups of caramel frappuccino and bubble tea, while others linger in shops selling everything from recycled clothing and gourmet coffee beans, or sit quietly reading along long tables in a bookstore.

In the atrium, where the fountain once stood, local artisans have set up tables to sell their jewelry, pottery, and other folk wares. Around them, children frolic as parents relax.

Those who know Miyako City well say it has evolved from its previous persona as a cathedral of consumption into a place to gather, socialize, and reaffirm the bonds of community.

‟These days, we want to spend time at a place that shares our values and isnʼt just about spending money,” says Hirohisa Hashimoto, who has worked in the mall for decades, and now owns a womenʼs clothing store there. ‟Miyako City is familiar. It makes us feel relaxed and comfortable.”

Hashimoto says that over the years, the mall has offered local residents a place to spend evenings or weekends, go on a first date, or even pursue careers. He says the mall has become an anchor for the community of downtown Miyazaki, the prefectureʼs largest city, serving the same function as a town square did in previous eras.

Hashimoto and others say this is why the mall is still able to draw crowds despite the rise of Internet shopping and the construction of larger malls and big-box stores on the city's outskirts.

Hashimoto, 64, says he has deep ties to the shopping mall. As a young man, he got his start in the fashion industry by working as a salesman, delivering clothing to shops in Miyako City. Seven years ago, when he decided to strike out on his own by starting a clothing store. He chose Miyako City as the place to do it.

He says he wanted to make his own store, Coco Lond, a place where families can feel comfortable being together and just browsing. He chose a decor that is urban-rustic: exposed concrete and air ducts juxtaposed with white-washed clapboard walls.

‟Miyako City has changed, but we still trust Miyako City because we grew up with Miyako City,” he says. ‟We feel an emotional connection with it.”

Miyako Cityʼs revival got a boost from Ichigo, the Japanese sustainable infrastructure company, which bought the mall in 2006. This autumn Ichigo completed a year-long renovation that brought in new tenants, removed walls to create open spaces, installed more efficient and environmental LED lighting, and added natural wood floors and ceilings. The atrium was converted into a forum for fairs, concerts, and farmerʼs markets.

The renewal is one of many steps that have prevented Miyako City from becoming one of the so-called dead malls that now dot American communities and have also started appearing in Japan. The mall faced that risk in the 1990s and early 2000s, when Japanʼs economy went into a long slide. For a time, Miyako City became a ghost town.

The secret to the mallʼs revival was recognizing the need to periodically freshen up the mallʼs appearance and add new tenant shops to serve the changing tastes of consumers, while also constantly seeking new ways to serve and strengthen the local community.

‟Miyako City is a centerpiece of the community, and we are working to keep being that,” says Hokazono, the man who visited Miyako City as a teenager. Since that first encounter, the mall has also been a centerpiece in Hokazonoʼs own professional life: He got his first management job running a steak house in the mall in the 1980s, and now oversees the mall itself as Miyako Cityʼs general manager.

‟Ichigo has a long-term commitment to the mall, and to Miyazaki,” he says.

Today, the mall tries to do that in many ways, including by offering a range of services in addition to shopping: a health clinic, nail salon, childrenʼs indoor playground, a food court, and a womenʼs-only hot yoga studio called Curves.

‟Miyako City is like an entire town, all inside one big building,” says Kenji Iwakiri, who owns a restaurant that serves okonomiyaki, a popular Japanese comfort food.

Iwakiri, 71, has run his restaurant, Tonpei, since the mall first opened. He does his own cooking, wearing a 1950s-style U.S. diner cap while mixing the okonomiyaki egg batter, cabbage, and toppings in front of customers who sit along the counter.

Over the decades, he has watched the people of Miyazaki grow up. One of the most satisfying experiences, he says, has been when men and women come in and ask if he remembers them.

‟‛I used to come here as a kid with my parents,’” Iwakiri says they tell him. ‟And now they come bringing their kids and grandkids. Theyʼre happy weʼre still here.”